Sing Sing and the Redemption Found in Art

Sing Sing (2024) redefines prison drama, showing art as redemption. With a cast of formerly incarcerated men, it highlights theater’s power to transform lives and restore humanity.

I knew immediately, based on the little context I consumed before watching Sing Sing(2024), that it would do something special. It ticked all the boxes, ones I didn't even know existed, like a predominantly unheard-of cast, with actors playing themselves on screen, and the addition of the brilliant Coleman Domino. While Domingo (starring as the wrongfully imprisoned Divine G, a real person and mastermind behind the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program) is enough to have me sat, its deviation from what is typically expected of an “American prison drama” pulled me in even further. There's no extensive escape plan, involving coded maps and plastic spoons, no evil warden or bad blood between inmates. The drama that unfolds in Sing Sing doesn't come from a series of plot functions but from the very core of the characters themselves, where complexities and realities are laid bare to the audience in a way so striking, that the perspective the film offers is life-altering. I knew the movie would be good. And it was. But not only was Sing Sing good, it was transcendent, and all that can be gained from the film, what it insights and inspires, is reinforced by the way it is filmed itself.

The idea that art contains the possibilities for redemption is a well-known concept. Art therapy continues to provide patients with healthy, productive coping mechanisms, giving them an outlet for issues ranging from trauma to stress. It's also a powerful tool for rehabilitation and this is shown in Sing Sing. RTA isn't seen as therapy, or even as rehabilitation, not when to the characters, it's the only thing to do in a place void of pastimes. Still, we see the effects of the program, of art therapy, as the incarcerated men are able to find a purpose in their confinement by creating, becoming, and embodying art. While there is a sense of hope and positivity deeply within the film, they don't let you forget that it’s still a prison film, one that blends this hope with the realities of prison, and the criminal justice system.

We watch the film from an undeniable standpoint of privilege, free to consume whatever media we feel inclined to and able to take action based on free will, not predetermined and set on a schedule. As free citizens, able to traverse the world as we please, we are entirely open to art, to the ability to create and invent. We can take in art as we please, and since it’s so accessible, we tend to disregard it. In Sing Sing, art and theatre are the only escape from the monolith the system is built to enforce, and it is an escape that not only gives the characters respite from the expectations of the oppressive system but gives them the chance to see the impact art can have on their lives. The fact that the cast is mainly formerly incarcerated men only doubles down on this aspect, as these men found themselves as actors in RTA, and then went on to act in the critically acclaimed film, even though they portray themselves. Clarince Maclin, known in the film as Divine Eye, delivers a performance so outstanding that to find out he wasn't an actor all along is shocking, and contributes to this. Sing Sing makes continuously clear the possibilities that we receive through an openness to art and its healing abilities. If the characters of the film were able to find liberation through art within their limiting environment, why can we not utilize the access we have to art in a similar fashion?

Sing Sing is not just a glimmer of hope, one that shines and twinkles in the distance, but a blinding ray of it. What sets the film apart, is that while the performances are outstanding, the camera and the talent work in tandem, and both take on the brunt of the message they wish to elucidate. Director of Photography Pat Scola filmed the entire drama using 16mm film, rather than digital or even 35mm, and this choice structures the film's profoundly emotive narrative. It isn't just the characters, with their heartfelt, honest monologues and the actors’ immaculate performances, that spearheads the complexities of the storytelling, but it is the shots themselves that communicate something, even without the dialogue of the characters.

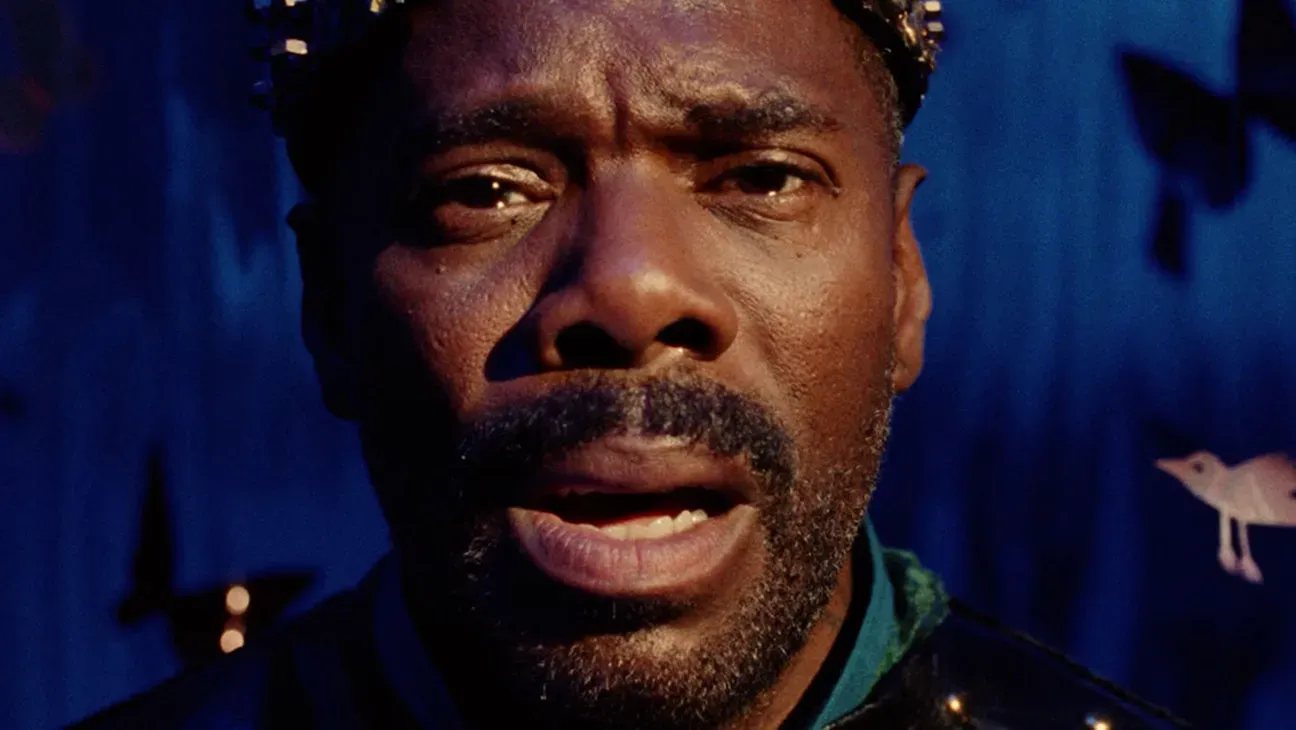

The film opens up with Divinge G as he speaks to the audience, a unique monologue, one that builds until we see his face, etched with pure rapture and passion, as he delivers his last lines. What we are shown in the exposition makes it clear that already, this is not gonna be your common “prison” flick. Even as we are led through the prison, seeing shots of inmates traveling downstairs, lining up, and drilling in the yard, there is an essence there, the same as the emotion that poured through Divine G’s face, and out of the screen. This essence follows the film like a phantom, infecting even the most despairing moments with an underlying warmth. This warmth that follows what is typically depicted as an oppressively cold environment looks a lot like hope, and it's there the second the film begins.

Sing Sing does not give us the fluorescent lighting, grey walls, and bleak cells that we expect to see. The film shows us the prison's green surroundings, the sun's warm yellow light, and bright laughter. We see decorated cells, marked with personalities like homes, or as close to home as possible. Characters banter and bounce off each other, supportive and uplifting. The small ensemble, a team of under 20 actors, are the only characters we follow, and by defying the usual stereotypes that dictate the genre, the characters are complex from the jump. Divine Eye threatens another inmate and then casually recites King Lear. As we follow this small group experiencing the prison through RTA, their connections with each other, and their journey towards understanding their own pain, the very way we see the prison is in line with their own experiences of growth inside it.

Sing Sing does not glorify incarceration. It doesn't do anything near it, not when it depicts the devastating realities of these men’s lives. While the reality it shows may not be the same dystopian, dehumanizing environment we are used to, it is not due to the prison itself that it appears this way. Sing Sing displays the hope and passion of the inmates, ones who are given the chance to find a purpose within art, and who are able to see their experience within the prison in a different light, thanks to RTA. Sing Sing does not romanticize prison, not when it only serves as a reminder that incarcerated people are people just as we are. The film reinstates the very essence of humanity within a place that’s sole purpose is to diminish it. We never learn what the inmate's crimes are, and there is no curiosity around it, because what we see depicted are not prisoners, but humans.

Throughout the film, we are given an intimate view into the character's inward journeys, as they find the parts of themselves that resonate with the characters they learn to play. Sing Sing insists that there are no excuses. Art and inspiration can be found anywhere, utilized anywhere, and sometimes, constraints and limitations are the key to creativity. The members of RTA use storytelling as a way to learn more about themselves, and in turn, they inspire an audience with no limitations, to use their resources to a similar end.

The Art Newsletter

Creativity. Culture. Community.

Every Thursday, we send a carefully curated drop of stories, tools, and creative insight for the next generation of artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers, and thinkers.

From cultural commentary to personal reflections, viral trends to overlooked gems. We cover what’s happening and what matters. Want local updates too? Join our Austin list for events, meetups, and opportunities.