Why You Should Never Skip Intro

A television show's opening credits give free reign to creativity and style, leading to stunning sequences that become indispensable parts of their series.

In their ongoing mission to chip away at artistic integrity in service of their almighty algorithms, streaming services have standardized the practice of making a little box pop up in the bottom right corner of the screen at the start of every single episode of every series they feature. “Skip Intro.” It is a strange practice for these platforms to actively encourage people not to watch portions of their own shows. But this seems to be a rather popular feature. Apparently, there are a good number of people who are just so busy that they absolutely cannot spare an extra minute or two to appreciate what is often the most creative segment of an episode. TV title sequences are not optional bonus features. They are parts of the episodes, integral parts at that. They are a means for a show to set a tone, to tell a story, to assert its identity. And beyond that, they are inventive, captivating works of art. So don’t skip them. Ever.

It has always been an uphill battle for title sequences to gain respect, going back to before their emergence as staples of television. For decades it was common practice for movie theaters to keep their curtains closed as the opening credits, which were viewed as inessential preamble, played. The curtains only opened when the opening credits ended and the so-called real film began. That changed in the 1950s thanks to the work of designer Saul Bass, who singlehandedly revolutionized opening credits (as well as movie poster design) in his work with directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Otto Preminger. Bass’s title sequences were short films unto themselves with designs that established the aesthetic identity of the film and immediately set the requisite tone. His opening for Vertigo is particularly extraordinary, with its close-up on a woman’s face and spiraling shapes within her eye set to Bernard Herrmann’s hypnotic score perfectly encapsulating the film’s dizzying eroticism. It was his work on the 1955 Preminger film The Man with the Golden Arm, though, that changed the perception of title sequences when its prints were sent to theaters with a note attached demanding that projectionists open the curtains before the credits. The broader message Bass and Preminger sent was that opening credits were an essential part of the film itself, not merely an appendix there for legal reasons, and that they deserved to be viewed with the same respect as any other part of the film.

The consideration Bass and others worked to make sure a film’s opening credits received should carry over to those of television shows, which have now become the primary home for creative openings. Opening credits in movies, though still sporadically present, have largely fallen out of style, with stylized credits sequences usually pushed back to the end of the film. On TV, the stylized title sequence remains a traditional practice, though nowadays those too are declining as more and more shows opt to use only a title card and put the credits either over the beginning of the episode or entirely at the end. Plenty of shows still stick to the full title sequence, though, or at least to one that covers all of the cast credits, and in these sequences there is still remarkable artistry on display.

Like the movie opening credits that Bass designed, one of the primary functions of a TV show’s title sequence is to establish the tone, the overall vibe of the show. Any title sequence worth its salt does this, and it doesn’t take a high-concept animation to make it work. Stranger Things creates an addicting vibe with opening credits composed of nothing but the letters that make up the show’s title. But its simple, analog nature, with the film grain and the flickering red neon light of the letters that bleeds past their boundaries, is a perfect expression of the show’s nostalgic retro vibe, recycling the style of the ‘80s movies it is based on, and infusing through the flickering red and the synth score the cozy eeriness which is the show’s tonal home. A show like Twin Peaks relies on the tonal statement its titles make each week. For a show that delves so deeply into surrealism and cosmic mystery, the title sequence focusing on the area’s natural beauty keeps the show grounded, attached to the warm beating heart of its setting that needs to be there so the darker elements can play off of them.

Beyond just establishing a vibe, title sequences can be storytelling devices unto themselves, contextualizing how we view the body of the show. The Simpsons is probably the most famous example, with its opening showing how each member of its title family finds their way home to the couch and thus providing quick characterization. A similar journey-home structure is used in the title sequence of The Sopranos. Emerging out of the Lincoln Tunnel, we follow Tony’s route home, seeing the New York skyline through his car’s side mirror as he goes onto the New Jersey Turnpike. Such an image signals the show’s departure from the big time New York mob stories like The Godfather, the stories Tony and his underlings are obsessed with and with which the show puts itself in constant conversation. We are literally putting New York in the rearview mirror and heading somewhere else. The title sequence paints Tony as an important, regal character by showing only bits and pieces of him. We see a silhouette of him lighting his cigar, a close-up of his hand on the steering wheel, his eyes through the rearview mirror. The final reveal of his face does not come until the final shot of the sequence. We do, however, focus on the world Tony is driving through, the new age gangster setting that takes the place of Little Italy, with its factories, railyards, and pizza joints. The whole sequence gives the impression of a king surveying his territory, giving us a primer on the show’s world and the man who rules it.

Another series which uses its title sequence as a storytelling device is Severance. Certainly, the trippy visuals do plenty on their own to establish the show’s befuddling mysteriousness, but they also represent many of the show’s themes, as we see a struggle for balance between Innie and Outie Mark, the events of each of their lives affecting that of the other in ways neither is fully aware of. The images of a black rot seeping out of Mark’s trash bin that comes to resemble his shadow and of Outie Mark lugging his Innie around as though he were a large balloon in a strong wind serve as snapshots of the show’s psychological musings. The second season’s title sequence builds on these ideas by having Mark’s Innie and Outie begin to interact and discover each other’s worlds to reflect the two personas merging in the show. Then there is The Americans, whose thirty-second title sequence serves as a perfect thematic precis even without the use of any of the show’s characters or scenes. It juxtaposes American and Soviet cultural imagery, cutting back and forth between them frantically and putting them side-by-side in the same frame until we end with an explosion. It represents how our two main characters become increasingly torn between their American and Russian identities until they finally collide.

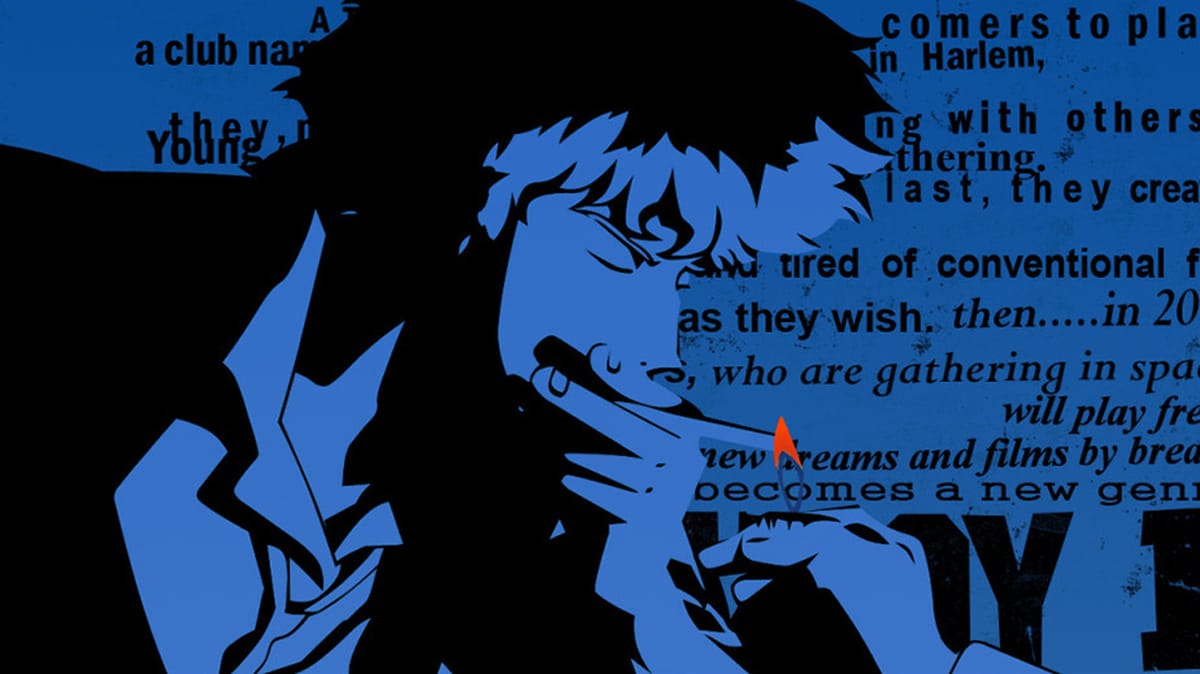

Put it all together, and you end up with the deepest function of a show’s title sequence: as a statement of the show’s identity. Identity runs deeper than just tone or themes, it constitutes the essential nature of the work. One show that makes a real statement with its title sequence is Monty Python’s Flying Circus. It features a completely nonsensical animation by Terry Gilliam, with no apparent meaning or logic, where every action seems totally random as though pulled out of a hat. This is the show telling us to throw out all expectations. Anything can happen, nothing is off the table, and there is absolutely no guarantee that any of it will make sense or have a punchline. It was a groundbreaking form of comedy, and it’s all present in the opening titles. The idea of proclaiming the show’s identity through the opening titles was taken rather literally by Cowboy Bebop, which incorporates into its title sequence a block of text that explains the concept of the show as a fusion of science fiction with the principles of jazz. But there is so much more to Cowboy Bebop’s titles. They accomplish just about everything discussed so far. The fast-paced visual collage and the riveting music establish the show’s colorful and eclectic style. The images give us snapshots of the main characters and introduce us to the vehicles and technology of their world. It is a minute and a half-long explosion of style, concept, and high-octane funk. It might be my favorite TV title sequence of all time.

Using the opening titles as a declaration of a show’s identity also gives the showrunners a powerful tool: the ability to alter the show’s identity by changing the title sequence. Game of Thrones famously used its opening credits as an exposition tool to give viewers a crash course in the geography of Westeros, and would change the intro episode-by-episode based on where the important action was taking place that week. But changes can go deeper than that. The Leftovers, for instance, completely overhauled its title sequence between the first and second seasons. The first season’s opening credits showed a large fresco depicting the show’s central disappearances as a biblical scene, establishing the show as a highly serious, dramatic work. That fit for the season, which was rife with the characters’ pain and grief. But after the first season, the show took a turn into more absurd territory and moved from focusing on the grief itself to its characters’ attempts to build something new out of it. So in the second season, the opening credits were about as different as you could imagine. Instead of biblical paintings of people wrenched away from their loved ones towards the heavens, we get innocent photographs of families and friends in tender moments: going sledding, jumping into a lake, dancing together at a party, except at least one of the people in the photographs isn’t there anymore. The outline of their body is, but it is filled with an image of the stars, or raindrops, or clouds. Instead of the high drama of Max Richter’s score with its strings and choral voices, we get a folksy country song with a woman singing about not wanting to know what happens when she dies. The pain and loss is still present, but instead of being front and center screaming at you, it exists more latently, calmly reminding you that it’s still there. It is a perfect match for the show’s change of tonal direction.

The changes in a show’s title sequence can also work to build a broader statement across all the different sequences. This is what happens over the five seasons of The Wire. The general concept for the title sequence remains the same throughout the series: a montage of the various details that make up Baltimore and a police wiretap. But the images used change season to season to reflect the institution each season focuses on. Season 1’s intro focuses heavily on images of the drug trade, Season 2 has images of the city docks and their shipping containers, Season 3 has images of city hall, etc. In addition, the music in each season’s title sequence is a different artist’s version of the song “Way Down in the Hole.” Each title sequence works just fine on its own, but together the five openings embody the show’s main argument. By having the specific images and sound change but the fundamental concept and song stay the same, these opening credits embody the show’s thesis that true social reform fails, because even as superficial changes are made – new mayors are elected and new police commissioners appointed – the fundamental systemic issues still exist and prevent any real change.

Shows like these where changes in the title sequence reveal the deep workings of the show highlight the importance of watching the opening credits every single episode. A change in the opening credits can signal a drastic shift in the show, and the impact does not come if you only watch the title sequence a couple times and then skip it the rest of the season. More generally, letting each episode air its title sequence makes the episode more of its own individual unit, and helps prevent the sludging together of episodes that can come so easily from binging a show. But really, these reasons should not be necessary to persuade you to let the opening credits play, because those credits are as important a part of the show as any individual scene. They set the show’s tone, they can give insights into the story, they serve as statements of the show’s identity, and they are wonderful works of art in their own right, avenues where traditional stylistic guidelines are discarded and for a couple minutes a show can do just about whatever it wants. So let yourself enjoy what it chooses to do with that opportunity.

The Art Newsletter

Creativity. Culture. Community.

Every Thursday, we send a carefully curated drop of stories, tools, and creative insight for the next generation of artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers, and thinkers.

From cultural commentary to personal reflections, viral trends to overlooked gems. We cover what’s happening and what matters. Want local updates too? Join our Austin list for events, meetups, and opportunities.