Imperfect Days

It's a new dawn, it's a new day, it's a new life. And in Perfect Days, feeling good requires risk and active engagement, not just a peaceful routine.

Most of the commentary I’ve found on Wim Wenders’ 2023 film Perfect Days characterizes the movie like this: it’s a slice of life drama without much of a plot, where we just watch our main character Hirayama go about his life for a handful of days. We observe the satisfaction and meaning he draws from simple tasks, including the dedication he applies to his job cleaning Tokyo’s public toilets. We observe how he takes note of all the small details throughout his day: the atmosphere of early morning air and the shadows of rustling leaves. In just watching Hirayama enjoy the simple beauties of everyday life without hunger for anything more, the film shows us how to be more attentive to the world around us and the hidden joys of our lives, to put aside our incessant hyperactive desires and appreciate what is wonderful about right now.

This characterization of the film is not essentially wrong, but it is incomplete. For a film so focused on simplicity, Perfect Days is much more complex than it lets on. Beneath the film’s celebration of quotidian beauties is an ethical investigation of how we ought to pursue the good life, an investigation whose depth comes from exploring the limits of the serene life Hirayama has built for himself. It is my contention that contrary to the dominant characterization of the film as a plotless depiction of a static character, Hirayama in fact has an arc centered on leaving his comfort zone and cultivating a more active engagement with his life.

The film’s first 28 minutes acquaint us with Hirayama’s daily routine. He shaves, waters his plants, and grabs a coffee from a vending machine before leaving for work. He selects cassette tapes to play as he drives between locations where he cleans each toilet diligently. He has lunch in a park and takes a picture of the treetops there on an old film camera. After he gets off work, he bikes to a bathhouse and then to a bar for dinner. Finally, he reads at night before drifting off to sleep.

This first day which the film spends almost a quarter of its runtime taking us through in detail serves as Hirayama’s baseline, his ideal “perfect day” that he seeks to repeat again and again. And it does seem like a perfect day: peaceful, full of myriad little joys. To accentuate the serenity of Hirayama’s life, the film even gives us a point of comparison. The first ten minutes of the film have no dialogue, and we quickly get comfortable with the attentive silence of Hirayama’s life. Then Hirayama’s partner Takashi comes rolling in and just will not shut up. He can do nothing but complain about his job and all the inconveniences it brings him. He questions why Hirayama puts so much effort into cleaning the toilets when they’re just going to get dirty again anyway. He hardly pays attention to his own work and is instead glued to his phone.

Takashi clearly does not get it. He is concerned only with himself and the trifles of his own life and does not pay attention to the world around him. He cannot understand the value of hard work for hard work’s sake, cannot see his work as anything more than a menial job to get over with as quickly as possible so he can move on to other things. He is completely disconnected from the life he is actually living. Next to a character like this, the appeal of Hirayama’s approach to the world becomes evident.

What Hirayama is after in his life, to put it in more formal terms, is what the Ancient Greeks called “ataraxia.” The word doesn’t have a direct English translation, but words that come close are “tranquility” or perhaps “unperturbedness.” Ataraxia is an essential concept in Stoic thought, where by focusing on the aspects of life one can control (namely, one’s values, beliefs, and desires) instead of the aspects one cannot (namely, the machinations of the external world), one can become impervious to misfortune, eliminating irrational desires that lead to anguish and living with a stable inner peace that makes one better able to appreciate the good things as they come. This is exactly what Hirayama has cultivated in his simple routines; he has dissolved the desire for more material things, and instead oriented his psyche to appreciate his life just as it is, to savor each and every good thing about it. This Stoicism on Hirayama’s part has given him steadily joyful demeanor.

What we begin to notice, though, as Hirayama repeats his routine day after day, is that he treats this routine like a dogma. His bathhouse, his regular bar, his bookstore, these are not so much expressions of a man seeking out the joy in every corner of his life as they are a safe, comfortable path he has carved out for himself. Hirayama depends on his routine to keep him tranquil, and is reluctant to divert from it. Most indicative of this dogmatism is Hirayama’s self-enforced silence. He is by nature not very talkative, but in several scenes where Takashi tries to make conversation with him, his silence even in the face of a direct question becomes unnatural. Silence here seems to have stopped being something that occurs as a result of Hirayama’s calm attentiveness and started being something he actively tries to maintain even when it makes no sense to do so.

Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with sticking to a comfortable routine, especially when that routine offers the peace and satisfaction it gives Hirayama. But clinging so closely to this routine does mean that Hirayama is limiting his range of possible emotions and experiences to that which his routine offers him. And as the film goes on, it starts to show us these limits. Part of ataraxia is emotional stability. As part of the effort to eradicate erratic, unstable emotions, then, the overall intensity of the emotions one feels gets somewhat lessened.

This we see in the film, as the younger characters like Takashi feel their feelings much more strongly than Hirayama does. At one point Takashi’s friend Dera shows up positively thrilled to have found him and squeezes Takashi’s ears, an old custom between them, Takashi explains. Such a display of affection is far beyond the bounds of Hirayama’s tranquil life. Even more revealing of the younger characters’ greater emotional amplitude is the strong reaction Takashi’s girlfriend Aya has to Patti Smith’s song “Redondo Beach.” Hirayama is the one who has actually made collecting and listening to this music a major part of his life, yet we have not seen him have such a visceral reaction to that music.

A more serious limitation of Hirayama’s reliance on routine is the solitude it forces upon him. Now Hirayama is a totally self-sufficient person, and there is nothing in the film to suggest he is especially lonely, but it is still concerning just how little interpersonal interaction there is in his life. It is not as though there is no opportunity for it. The owner of the bookstore he frequents offers a personal opinion of each of the books he buys. The bar he frequents has other regulars there to watch and chat about baseball games. Yet Hirayama maintains his self-enforced silence, refrains from getting into a conversation. Even at his favorite restaurant where he is on a first-name basis with the owner, he shies away from any sustained interaction with her or the other regulars.

Why might Hirayama be so averse to interacting with other people? Because doing so is risky, and Hirayama has built his life around a stable routine where there are no uncertainties. The core of Stoicism is staking your happiness only on the things you can control. But other people are inherently uncertain factors, and to depend on them for your own happiness is to make that happiness, at least in part, out of your control. So Hirayama builds a life which does not rely on other people, where he can guarantee his happiness through his own attitudes and behaviors. The problem, of course, is that interpersonal relationships are an essential part of being human, and Hirayama, in his pursuit of self-sufficiency, is cutting himself off from that.

After the first day we follow Hirayama, the film begins gradually introducing elements that disturb Hirayama’s routine, shaking him out of his rhythm. He has to bang the vending machine in the morning to get the coffee to come out. He finds in one of the bathrooms he cleans a note left by a stranger who has started a tic-tac-toe game, and puts his own move on the note before leaving it where he found it. Most significant of these early disturbances is his excursion with Takashi and Aya to a store where Takashi hopes to sell Hirayama’s collection of cassette tapes. After Hirayama begrudgingly lends Takashi money instead, he has none left to spend at his regular bar and has a ramen bowl at home.

But the biggest shock to Hirayama’s system comes when his niece Niko shows up at his house unannounced. In spending a few days with her, Hirayama is forced to reformulate his approach to the world. Most notably, he has to interact with another person for a significant amount of time, which in turn forces him to talk beyond a few sporadic mutters. But more than that, Niko’s energy and exuberance forces Hirayama to look at his routine through new eyes. Niko has an active attitude towards the world. She doesn’t see it, like Hirayama seems to, as something that she moves through and observes, but as something she participates in. Just as Niko learns from Hirayama the value of paying attention to the world, Hirayama learns from Niko the value of active engagement, not just passive appreciation.

One of the film’s most interesting moments comes when Hirayama and Niko ride their bikes to the center of a bridge and look out at the river below. Niko asks if it goes all the way to the ocean and Hirayama confirms that it does. “Wanna go?” Niko asks. “Next time,” Hirayama responds. When Niko asks when exactly next time is, Hirayama specifies, “Next time is next time. Now is now.” There are a couple ways to view this exchange. One might interpret it as Hirayama trying to show Niko the importance of the present moment. Rather than immediately jumping to some other desire, to some other experience she is eager to have, she should focus on the experience she is currently having. Now is now. On the other hand, this is another instance of Hirayama being reluctant to do something outside of his normal routine, neglecting the opportunity for a new experience. This scene makes apparent both the advantages and limitations of Hirayama’s approach to life, resulting in the closest he gets to an actual articulation of that approach. The scene ends in something of a compromise: the two bike off, not headed to the ocean, but Niko turns Hirayama’s mantra into a call-and-response song, infusing the moment with a little active, adventurous character. Even within a stable routine, the scene suggests, there is still room to turn a moment into something unique.

The following scene gives us our only real information about Hirayama’s backstory. Hirayama and Niko return to his house, and Niko’s mother is there waiting for them, ready to take Niko home. She has clearly not seen Hirayama in a long time. She has come in what looks like an expensive car with her own driver, and asks Hirayama in disbelief if he is really cleaning toilets for a living. This is enough to infer that Niko and her mother are quite wealthy, and that Hirayama presumably comes from that same wealth. His simple lifestyle is not merely the most he can manage given his means. It is something he actively chose.

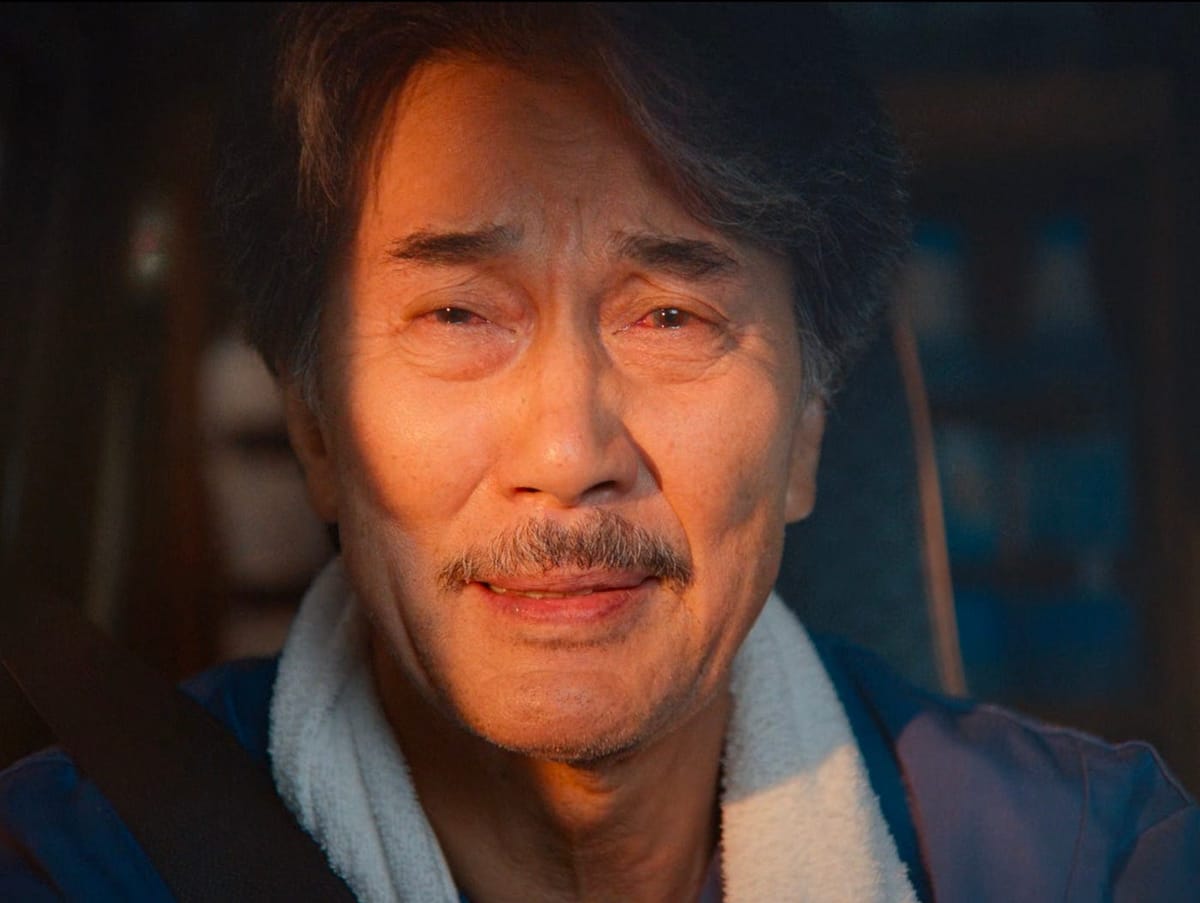

Niko’s mother mentions that their father cannot recognize anything anymore and implores Hirayama to visit him in the nursing home. “He won’t act like he used to,” she says. The implication here is that Hirayama and his father have a troubled relationship, and it is not unreasonable to infer that there may have been some crisis or major falling out that drove Hirayama away from his family, away from their affluence, and into the life he is now living. This is significant; it signals that Hirayama’s life, pleasant as it is, does not come solely from a positive desire to cultivate happiness. It is also a retreat away from something, a cocoon that keeps him safe from something still very sensitive. His immediate, characteristic refusal to see his father signals that sensitivity. The emotional weight of the moment finally gets to him, and for the first time he initiates connection with another person, hugging his sister goodbye. As they drive off Hirayama starts crying. His ataraxia has been pierced and he has his first real emotional outburst of the film. He is feeling something he has not felt in a long time.

From here, the film continues disrupting Hirayama’s routine, more vigorously now. The next day, Takashi calls Hirayama to tell him that he’s quit, and Hirayama will have to cover his shift. Hirayama, ever the passive appreciator of things as they are, now has to relentlessly call his bosses to demand they find a replacement for Takashi because he will only cover his shift once. It works; the next day a new worker has reported for duty.

In the film’s final major episode, Hirayama’s plans to go to his usual restaurant are foiled when he walks in to find the owner in a private moment, tearfully embracing another man. Hirayama goes instead to the river with a few drinks and a pack of cigarettes, and gets approached by the man from the restaurant. He introduces himself as Tomoyama, the ex-husband of the restaurant owner. He has cancer that has just metastasized, and he felt the need to see his ex-wife again. He and Hirayama stand together by the river for a while, sharing a drink.

Tomoyama wonders out of the blue if shadows get darker when they overlap, lamenting that there are so many things he will never know. Suddenly Hirayama has an idea. He beckons Tomoyama to stand beneath a streetlight and tests the question, overlapping their two shadows. Then Hirayama announces a game of shadow tag, and the two begin gleefully chasing each other’s shadows around. It seems like a small moment, but this is a massive shift in Hirayama’s behavior from the start of the film. Where before he would have kept to himself and just taken note of the world around him, now he actively builds a brief friendship with another person and spontaneously comes up with a new activity that has him energetically participating in the world with others.

Hirayama wakes up one more time in the film. Like always, he stops and takes a breath when he first steps outside and selects a cassette tape to play as he drives to work. The song today is Nina Simone’s version of “Feeling Good.” As it plays, Hirayama’s peaceful demeanor erodes in into intense emotion in a two-minute close-up until his eyes are red with tears. We are far away from the ataraxia that keeps one in a calm, stable emotional state and are witnessing feelings as strong as the movies can depict. What has happened?

Put simply, Hirayama is feeling all at once the cumulative weight of all the new experiences he has had over the course of the film. This is a man who lived a life that was peaceful, that was joyful, but that was entirely closed off. Everything was determined, everything was secure. There was no risk, no vulnerability. And now, over the past several days, he has opened himself up to all those aspects of life he had previously sealed off and is undergoing that sublime, overwhelming rush of being human. He has seen the sunrise over Tokyo many times, but today it feels different. Previously, that sunrise was part of an iteration of the same perfect day Hirayama sought to savor again and again. But now, as Simone sings, “it’s a new dawn, it’s a new day, it’s a new life for me.” And he’s feeling good.

It is entirely understandable that the most common reaction to Perfect Days is an admiration of Hirayama’s simple life and the joy he manages to squeeze out of every corner of it. Most of us watching the film are probably more like Takashi, caught up in our dissatisfactions and desire for more. In that regard the film is a potent reminder of the value of slowing down and paying attention to the world around you. But this is not all the film has to offer. For in the emotional journey of its main character, the film also stresses how life is not an object to be passively savored but an activity that begs for active engagement. It seeks a synthesis between the ataraxia of the Stoics and a mode of living more in line with Nietzschean exuberance. Part of living well entails risk and the uncertainty of not knowing exactly how things will work out for you. The film encourages us to make the most out of each day, but that doesn’t mean that the day has to be perfect.

The Art Newsletter

Creativity. Culture. Community.

Unlock independent analysis trusted by curious minds worldwide become a paid supporter and get access to our full content library. Every Thursday, we send a carefully curated drop of stories, tools, and creative insight for the next generation of artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers, and thinkers.

Join a global community of readers who never settle for surface-level stories.