Hundreds of Beavers Is the Video Game Movie We Need

Hundreds of Beavers Is the Video Game Movie We Need Hundreds of Beavers is a brilliant movie. I’ve written about it once already for this site, praising its creativity in the face of a miniscule budget and the escalating series of gags that stack on top of each other.

Hundreds of Beavers Is the Video Game Movie We Need

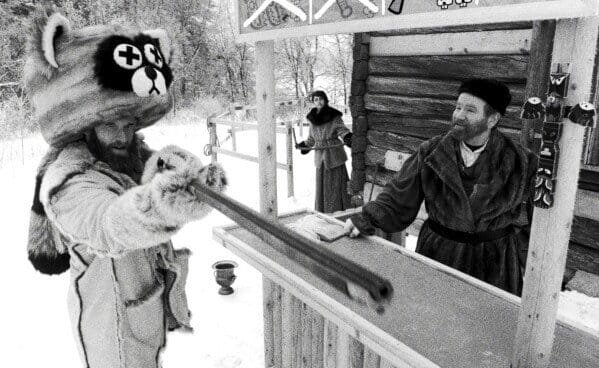

Hundreds of Beavers is a brilliant movie. I’ve written about it once already for this site, praising its creativity in the face of a miniscule budget and the escalating series of gags that stack on top of each other. Then I watched it again, this time in a theater with a crowd, and on second watch the video game nature of the film became unmissable. To be clear, Hundreds of Beavers is an original film not based on any pre-existing work, and thus not an adaptation of a video game. But it is still a video game movie. More specifically, it is a film that replicates the experience of playing a video game, of growing and skill and becoming master of the world you inhabit. As such, it can serve as a beacon to the many films to come actually based on video games, an indicator of how to successfully transfer that art form into the cinematic medium.

Video game movies famously do not have the proudest history. While the past five years are so have seen game adaptations with considerably more success than previously, from the TV adaptations of The Last of Us and Fallout to the Sonic the Hedgehog movies, these are the exceptions, and the vast majority of adaptations have fallen somewhere between forgotten and reviled. While the blame for this is often placed on a general lack of respect for video games as an art form leading to studios and directors not taking their source material seriously, there is a more fundamental challenge that most adaptations have failed to overcome. Video games are an interactive medium designed to incorporate their player as a participant, not just a passive observer. How do you take that essential aspect of a game and translate it to a medium where the audience is a passive observer? Adapting a game into a film or television series inherently involves stripping it of its defining feature. The Uncharted games, for example, are heavily inspired by the Indiana Jones films, in their globetrotting action-packed adventures uncovering lost civilizations and finding ancient artifacts. But the games add the critical element that you get to be Indiana Jones. You get to be the one solving the puzzles and navigating the dungeons and getting in elaborate chases, instead of just watching Harrison Ford do it. So when you take that video game franchise and turn it back into a movie, stripping away the interactive element, what are you left with? Just a hollowed-out knockoff of Indiana Jones with nothing to distinguish itself. One can be as faithful as they want adapting the iconography of a game – using the same environments, copying the cutscenes shot-for-shot, recreating entire levels on screen – but as long as they cannot find a way to preserve the interactive component, the final result is going to feel empty, at best like watching somebody else play a video game.

Hundreds of Beavers might be that film that finally found a way to fully translate the actual gaming experience into the cinematic form. It does so by structuring its narrative like that of a video game. Critically, though, this does not mean the plot of a video game, but rather the narrative the player experiences through their playing of the game. This is the important distinction, and the one that holds the key to successful game adaptation. The Mario games all have plots, usually about saving the princess, but these can hardly be considered a central aspect of the games. What the games are really about, experience-wise, is running and jumping across platforms. Open-world RPGs like Skyrim and Red Dead Redemption have a central story, but for many players this story is a secondary component of the game, and the core feature of it is just exploring the world, completing various missions, and growing in power. It is this kind of game that Hundreds of Beavers emulates. It has a threadbare plot about surviving in the wilderness and trying to win the hand of the Furrier, but the actual meat of the film is built around this same core experience: exploring the world and increasing in skill and power.

There are two key decisions the film makes that make the central power crawl narrative particularly immersive, that help preserve some of the interactive feel of a video game. The first is in the basically empty characterization of its hero, Jean Kayak. He does have a backstory as an applejack salesman that the film’s prologue establishes, but from the moment he emerges from the snow and the film proper begins, he is essentially a blank slate. He does not talk, he does not have a complicated psychology, his desires and emotions are simple and immediately understandable. He has about as much characterization as a plumber that jumps around yelling “Yahoo!” and so the audience can immediately attach to him as an avatar rather than having to regard him as a full character. The second important decision: having him fail over and over and over again. Most video game adaptations are in a hurry to get to the cool part where the characters have their iconic abilities and can cut through enemies like butter. But what they fail to realize is that those elements are only successful in video games because they are earned by the player. It takes work to master the right button combinations and learn the patterns of the world and the enemies within it. Beating a level is satisfying because you have died time and time again attempting it. The ultra-powerful stage is something players have to work towards, and that work, and the failure that goes into it, is what makes the power rewarding. Hundreds of Beavers is remarkably patient in its power crawl, spending around half the film following Jean Kayak in his totally helpless state where he fails at just about everything he tries. He does not catch his first beaver until 55 minutes in. He begins the film as Wile E. Coyote, where all of his best-laid plans inevitably fail because those are just the rules. But unlike Wile E. Coyote, he adapts. He learns from his mistakes, tries again, fails again, but fails better. So by the time he starts to get a hang of the trapping business, his successes feel satisfying. In this way, the film is able to replicate the satisfaction the player of a video game feels from their own increase in power.

This emphasis on constant failure and gradual skill improvement is the most important element to Hundreds of Beavers feeling like a video game, but there are plenty of other elements of the film that more obviously associate it with the video game medium. Like an open-world game, the film features a map, the trap line, that gradually gets expanded as our protagonist discovers more areas of the world. Our hero keeps an inventory of items which he trades to get better gear as the film progresses. There are even on-screen graphics keeping track of the number of beavers and other animals that he has. The film starts with our main character primarily dealing with low-level enemies in the rabbits before progressing to higher-level enemies in the beavers and wolves. The Master Trapper character is like a high-level player that you tag along with for a while, where you stand there uselessly as they decimate the enemies you have struggled with. The wolves’ cave functions like a dungeon that you cannot clear until you reach a high enough level. The saloon fight towards the end represents that point where you have reached such a high level that you can effortlessly carve through the enemies that had previously caused you so much trouble. Even the film’s style matches old-school video game language. The framing is usually two-dimensional, with each location essentially having its own screen and its own music. All of these elements help fill out the video game nature of the film and make it easier to associate the film with the video game medium, but on their own they are insufficient. It is the aforementioned progression of the hero that the audience vicariously goes along with that makes the film feel like a video game; the other elements only make it look like a video game.

The American film industry has a remarkable skill for always taking the wrong lessons away from its successes, so it would not surprise me if those looking to adapt video games saw the success of Hundreds of Beavers and concluded that sticking more faithfully to specific video game language would make better adaptations, perhaps by having health bars appear on screen or having characters crouch to avoid being seen. If anything, they should draw the opposite conclusion. Even with all its direct parallels to video game language, Hundreds of Beavers draws from many other sources which contribute to its brilliance. Most of its humor follows the logic of Looney Tunes, and many of its gags occur through editing, a tool video games do not have. Hundreds of Beavers is a video game movie, and the “movie” part is the more important one. The task of adapting video games, or any other medium, into films is one of translating, not of copying. It is about finding the essence of the game’s experience – the actual experience of playing it, not merely its plot and iconography – and capturing that essence through cinematic tools. Hundreds of Beavers, even without specific video game source material, understands that: it finds a cinematic form that can capture the essential experience of progress and growth that defines many video games, and the iconographic similarities to a video game are only icing. Other video game adaptors should aim for something similar, and by similar, I do not mean making the film a silent black-and-white Looney Tune with people in fur suits instead of CG creatures. I mean locating the core experience their game provides and finding an analog for that experience in the cinematic form. I honestly do not think there is much interest in merely putting video games on screen. I certainly have no desire to spend $15 going to a theater to see a Let’s Play video with movie stars. But taking video games and turning them into honest-to-god movies using the full scope of what a film can be? There, the possibilities seem endless, and most of them have yet to be explored.

The Art Newsletter

Creativity. Culture. Community.

Every Thursday, we send a carefully curated drop of stories, tools, and creative insight for the next generation of artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers, and thinkers.

From cultural commentary to personal reflections, viral trends to overlooked gems. We cover what’s happening and what matters. Want local updates too? Join our Austin list for events, meetups, and opportunities.