How Much Do Spoilers Really Matter?

Our spoiler-averse culture has reached a fever pitch, but is its terror justified?

Heads up: this article contains rampant spoilers throughout for various stories across history. Though if you want to consider seriously the idea that spoilers might not ruin stories, then you should keep reading anyway.

Let me start by putting my cards on the table: I am squarely spoilerphobic. My preferred means of watching a film or reading a book is to go in totally blind, often without even knowing what the basic premise is, just watching or reading it based on positive word of mouth or an interest in its creator. I stopped watching movie trailers (outside of the ones I can’t avoid at the theater) years ago and more than once have gone on a full media blackout, shunning recreational use of the internet for multiple days, to avoid details of particularly anticipated releases.

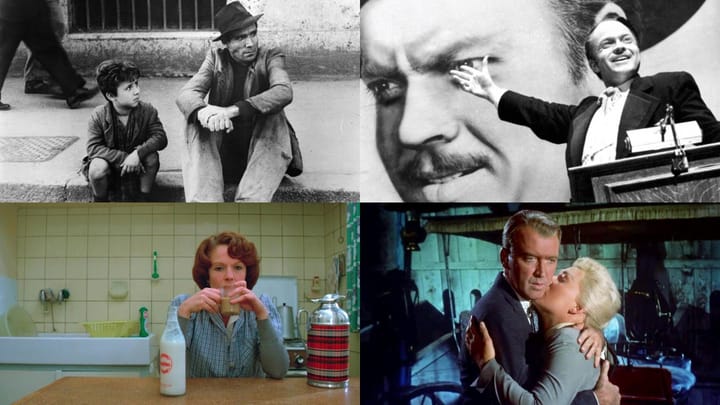

But that’s just my personal preference. Is it actually useful behavior in media consumption, conducive to more enjoyment? Is our cultural imperative to preserve secrecy among recently released media and berate those who give away their details justified by some real insight into stories and how we process them, or have we all gone a little crazy and collectively blown the impact of spoilers out of proportion? It seems absurd to claim that an ill-fated encounter with a spoiler can totally ruin your enjoyment of a great work of art, and plenty of anecdotal evidence suggest otherwise. I watched The Usual Suspects knowing the central twist and the first season of Game of Thrones knowing about Ned Stark’s death and didn’t find the experience of either significantly ruined.

From a historical angle, our spoilerphobic mania also seems irrational given how recent a development the very concept of a spoiler is. For millennia, popular stories tended to be based on myths the audience was already familiar with, and classical tragedies, from Sophocles to Shakespeare, often divulged their ending at the outset. The prologue of Romeo and Juliet, for example, is a synopsis of the entire play that explicitly tells us of the main characters’ eventual deaths. It’s worth giving real examination, then, to the impact spoilers may or may not have on our processing of stories, examination free of the inherent bias we have created just by labeling the phenomenon with a term as pejorative as “spoiler.” And in the vain of those classical tragedies, I’ll reveal the ending of my investigation up front: there is good reason to believe that spoilers do diminish one’s enjoyment of a story, but spoilers themselves are not nearly as harmful as the delirious culture we have built up around them.

If we want an objective account of how exposure to spoilers impacts our enjoyment of media, the best place to start is with actual scientific research. On the topic of spoilers the scientific literature is decidedly mixed. A 2011 study by Jonathan Leavitt and Nicholas Christenfeld at the University of California San Diego drew some attention by concluding that spoilers actually increase story enjoyment. They had subjects read short stories from different genres: “ironic twist” stories like “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” mysteries, and “more evocative literary stories.” Sometimes the stories were preceded by a spoiler-heavy introductory paragraph, other times they appeared as originally written, unspoiled. They found that across the board, ratings for spoiled stories were significantly higher than ratings for their unspoiled counterparts. The explanation Leavitt and Christenfeld posit for the results is that spoilers increase a reader’s perceptual fluency of the work. Essentially, people tend to enjoy stories more when they are easily able to comprehend how the narrative works. By knowing the final reveal ahead of time, they can then read the story better able to appreciate how the narrative builds to the reveal. They can “organize developments, anticipate the implications of events, and resolve ambiguities that occur in the course of reading.” This is the general argument of the spoiler-friendly crowd: knowing a spoiler ahead of time can help us better appreciate the narrative that builds to it.

However, the story here is not so straightforward. In 2015, Benjamin Johnson and Judith Rosenbaum attempted a replication of Leavitt and Christenfeld’s study and got the opposite results. Their study was more thorough: they used the same methodology of having subjects read short stories, sometimes spoiled and sometimes not, but rather than having subjects merely rate each story on a scale of 1 to 10, they employed a longer questionnaire aiming to capture different aspects of enjoyment: suspense, immersion, emotional impact, etc. Pulling on different theories of media enjoyment, they hypothesized that unspoiled stories would rate higher in suspense and fun, aspects of enjoyment characterized by the buildup and then release of excitement, whereas spoiled stories would rate as more thought-provoking and leave a longer-lasting impact, a separate aspect of enjoyment they label as “appreciation” more in line with the perceptual fluency theory Leavitt and Christenfeld support. However, in their study, unspoiled stories measured significantly better in most categories (in the other categories, data was inconclusive). The data of the scientific research on spoilers, then, mostly comes out as a wash. These studies give us useful theoretical bases on which to study spoilers, but we lack convincing empirical evidence for regular impact of spoilers either positive or negative. For the rest of this article, then, we have to resort to theorizing about spoilers from the armchair.

A useful task at this point would be to actually define the term “spoiler.” For there are many ways to consume a story already exposed to information about its forthcoming plot, and not all of count as being spoiled. Comparing instances of spoilers to these other methods of story consumption could help us nail down exactly what we think spoilers are ruining. One way to consume a story while knowing all the spoilers is by rereading or rewatching something you’ve already read or seen. You can experience a story blindly only once; every time you read or watch it after that you already know everything that’s going to happen. Yet rewatching a movie hardly counts as an instance of watching a movie spoiled, and this is because you have already had the full experience of watching it unspoiled. On subsequent viewing you may watch the film differently, knowing the twists ahead of time, but this is not watching the film spoiled, it’s just watching the film from a different perspective. So spoilers are not based on the audience having certain information ahead of time as much as they are on the audience not being able to have a pure experience of discovering that information. Once you’ve had that pure, unspoiled experience, you cannot subsequently be spoiled. The same reasoning applies to watching a filmed adaptation of a book you’ve read. The book is not spoiling the movie because you got the full experience of the story within the book, and the movie now provides the additional experience of seeing that story depicted audiovisually.

Something else that does not count as a spoiler: the prologue of Romeo and Juliet, or any of the other classical stories that divulge their endings at the beginning. For a necessary component of a spoiler is that it is premature, that it gives you information about a story you are not supposed to have at this point. But any author that tells their audience up front of events that will happen later on in the story clearly intends for the audience to approach their story with that information in hand. Knowing the ending before it happens is the desired experience, and hence what would count as a spoiler would be removing that information from the story, robbing the audience of the intended experience.

What a spoiler is, then, is when one is made prematurely aware of certain details of a story which they are not supposed to possess at that point, thus robbing them of the ability to fully experience the story the way it was designed to be experienced. This account helps us see what is actually so pernicious about spoilers: it is not the information they reveal, but rather the context in which they reveal it. What is harmful about spoilers is their “nakedness”: they reveal story information divorced from the aesthetic context that is meant to accompany the reveal of that information, thus divorced from the feeling that the reveal is supposed to bear. For instance, take the major spoiler of Oldboy: that Dae-su’s lover is in fact his daughter. In the film, this revelation is the centerpiece of the film’s climax, a highly emotional moment that resolves the film’s central mystery and provides the backbone of its melodramatic catharsis. But on the page, as I have laid it out just now, the information is nothing. There is no context for it, and hence it has no emotional effect. If you then watch the film already knowing this twist, the impact of the most important scene in the movie is blunted because you don’t get to experience the revelation along with Dae-su. It is thus the lack of context around a spoiler that is the really harmful element: if you were to read a full, detailed synopsis of a story that revealed all the plot information, this would probably be less harmful than finding the spoiler “in the wild,” since at least with the synopsis you get some of the experience of discovering the spoiler in the context of the story.

This account of spoilers, that emphasizes the way they prematurely divulge information instead of the information itself, also suggests a shortcoming of the studies described above that potentially leads them to underestimate the harmful effects of spoilers: in both studies, the spoilers were revealed to the subjects before they read the stories. But often the most devastating spoilers to one’s experience of a story are the ones they encounter during their experience of a story, when they are in the middle of a book, or a season of television, or between films in a franchise, and are already invested in the story. When you encounter a spoiler before going into a story, such as that “Rosebud was Kane’s childhood sled” or “Bruce Willis’ character was actually dead the whole time,” you have no conception of the story at this point and hence nothing is actively being ruined. When you go into the story, then, you can develop a frame of mind while reading or watching it which incorporates that piece of information. Your experience will still be diminished a bit because you are not experiencing the story as you are supposed to, but at least you can build a conception of the story that is consistent the whole way through. On the other hand, if you’re five books into Harry Potter and someone tells you Snape kills Dumbledore, or you’re working your way through the third season of Game of Thrones and then find out that Robb and Catelyn Stark die at the Red Wedding, then there is a lot more damage being done. You are already invested in the story and hence the information spoiled means something to you. You have already developed a frame of mind through which you are processing the story, anticipating how events might occur, and when you meet the spoiler, this pure experience gets shattered and you have to switch to a new means of understanding the story while you are in the middle of consuming it. These are instances in which spoilers can be extremely harmful to your experience of a story, not because of what they tell you, but because of how they tell it to you, and how they then prevent you from experiencing the story in the intended way.

I’ll be honest: I began my research on this article fully expecting to argue that spoilers are actually okay and not nearly as detrimental as we make them out to be. Now I feel a bit bad about encouraging readers to venture through this minefield of spoilers only to discover that they in fact can be quite harmful. Such is the price of intellectual discovery, I suppose. But examining spoilers themselves is only part of the story, for there still remains the issue of the culture that has developed around spoilers, and that culture has its own consequences separate from the impact individual spoilers have on audience experience of individual stories. For when we collectively freak out about not getting spoiled, and place that as a central aspect to enjoying a story, we train ourselves to look at stories in specific, spoiler-centric ways. Most notably, since we take spoilers to be the essential aspects of a story, and spoilers are almost always plot points, we place undue emphasis on plot as the key aspect of a story, something I take substantial issue with. I mentioned above that I no longer watch movie trailers, but that is not really because I am worried about plot spoilers. It is because those trailers usually contain many of a film’s best shots, best lines, best jokes, and those moments do not hit as hard in the context of the film if I’ve seen or heard them already. Under the spoiler-centered mindset with which we now view our stories, these aspects of a film become increasingly overlooked.

Spoiler culture in this way exacerbates the ongoing trend of art being transformed into disposable content. When our primary area of concern with media is not getting spoiled, we see the work not as a piece of art we are meant to grapple and engage with but as something we must immediately consume so that we can get our hedonic boost from the plot and then move onto the next thing. Emily St. James makes this argument in a piece for Vox: “ ‘unspoiled vs. hyper-spoiled’ is just two ways to look at the exact same thing: a relationship between art and the audience that is purely about consumption. […] The work has little value beyond its ability to act as a conduit for story and information.” Spoiler culture, incidentally, has done wonders for companies’ ability to market their projects: you have to see this movie on its opening weekend or it’s going to get spoiled for you. But this form of promotion treats the work itself as merely instrumental to the state of not-being-spoiled, not as the thing we are actually there to experience. And as the production, consumption, and discussion of art increasingly revolves around spoilers, we inevitably end up with work that leans more heavily on its spoilers, depends on them to have any value at all. Yes, spoilers can hurt our experience of an artwork, but if an artwork is so reliant on a particular plot point that a little information about it leaking out can ruin the experience entirely, that is a far bigger indictment of the work itself than those who spoil it.

Essentially, a positive feedback loop is occurring: spoilers can harm our enjoyment of stories, so we create cultural norms that guard against spoilers getting spread. But because of those cultural norms, we view spoilers as more important aspects of stories than they actually are. This leads spoiler culture to take a more central role in pop culture, which leads to art that leans more heavily on spoilers. This means that when spoilers do come out, they are more damaging, which then leads us to intensify our cultural norms around spoilers and adjust our interpretive practices around media to be even more spoiler-centric, and so on. So here is the conclusion I am drawing: spoilers, properly defined as information about a story prematurely delivered out of its aesthetic context such that they prevents the audience from experiencing the work as intended, do probably have negative effects on our enjoyment of stories. But our cultural frenzy around spoilers is only making the problem worse, and if we want both the dangers of spoilers and the plot-centered consumerist paradigm of art that comes out of spoiler culture to subside, then we all need to calm down. There is more to a story than its spoilers, and the more we recognize that, the less damaging spoilers will become.

The Art Newsletter

Creativity. Culture. Community.

Every Thursday, we send a carefully curated drop of stories, tools, and creative insight for the next generation of artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers, and thinkers.

From cultural commentary to personal reflections, viral trends to overlooked gems. We cover what’s happening and what matters. Want local updates too? Join our Austin list for events, meetups, and opportunities.

Comments ()