Betty Boop: Why a 1930s Cartoon Jazzy Diva Still Speaks to Us in 2025?

Beauty and jazz, escapism and reality

A century ago, while the silent competition between Walt Disney and Max Fleischer had raged for ages, little did the American animation industry know that a brand-new female cartoon star, Betty Boop, would be unexpectedly born at Fleischer Studios in 1930. She then quickly evolved into a fully developed series of cartoons and rose to global fame, leaving a timeless impression that resonates till now.

Back in those days when news of bankruptcy dominated headlines and streets filled with the unemployed, she became more than just entertainment, but a spark that lit up the financially depressed America. With her irresistible charm, flapper style, and unique jazz performance, Betty Boop gave people something else to talk about, to laugh at, to look forward to at a time when the world felt like it was falling apart at the next second.

Sound familiar?

Living in a post-pandemic world amid economic uncertainty, violence, and social upheavals, we grow obsessed with pop culture, scroll through TikTok and social media in 2025 for the same reason 1930s audiences flooded into theaters for a cartoon. We crave relief, escapism, and maybe even a little humble hope.

So here we go. Betty Boop isn’t just vintage or nostalgia. She’s a one-of-a-kind reminder of how pop culture keeps us afloat when real life attempts to drag us under.

One quick reminder though: this is NOT an animation for kids by any means. The show never shies away from sexual innuendo. Some early episodes, such as the famous “Boop Oop A Doop” (1932), depict scenes like sexual harassment, which could be relatively explicit and disturbing to some. Nevertheless, such assaults are eventually criticized rather than sensationalized in each and every episode as Betty fights them off. While the series primarily appeals to adult audiences and contains sexual elements, it does not deliberately condone the male gaze, though this claim remains subject to unresolved controversy. After all, scenes where cartoon women are chased and harassed for comedic effect are undeniably present and unsettling. How viewers conceive this narrative, whether as critique or crass humor, is crucial.

From Nameless to Stardom

Created by animator Grim Natwick in 1930, Betty Boop was originally designed to be the girlfriend of Bimbo the dog, a character created by Fleischer Studios during their experimentation with Talkartoons, a series of 42 cartoons featuring synchronized music and sounds.

Betty wasn’t born a shining star. She kicked off nameless and debuted as a weirdly hybrid character with half-human, half-dog traits. Unlike other anthropomorphic dogs, however, she was the first to do a swinging dance. Her musical talents gave the studio a glimpse of her potential to bring fresh creativity to the animation industry.

Recognizing her uniqueness, Natwick made her a human—or, more precisely, a “cute woman.” Over time, Betty Boop gained highly feminine characteristics and a striking appearance that had never been seen in previous animated characters. Her new character design featured a tiny waist, long lashes, crimson lips, curvy figure, high-pitched voice and flirtatious demeanor. These qualities became central to Betty Boop’s symbolic sexuality and popularity.

Returning to the Roaring Twenties

Betty Boop’s style was deeply influenced by the 1920s Jazz Age. Her short red skirt, black thigh garter, oversized hoop earrings and high heels highlighted the bold aesthetics of the flapper movement, showcasing a carefree and open-minded spirit.

In comparison to earlier female cartoon characters, Betty Boop appeared much more revolutionary. In Popeyes the Sailor Man, for instance, we meet Olive Oyl, Popeyes’ girlfriend. When debuted in 1919, Olive dressed in a long-sleeved top, floor-length black skirt, and heavy boots. On the other hand, Betty Boop, whose daring style revealed her thighs and chest, challenged the traditional expectations of how “good” women should look and emphasized the free gender values of the flapper culture. This contrast signals a broader cultural shift in the portrayal of female cartoon characters as they went from conservative, domestic figures to confident and liberated individuals. On that note, we may consider Betty both feminine and subtly feminist.

Her signature look came to an end, however, as Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America enforced the Hays Code in 1934, restricting what can appear in pictures with a list of “don’ts” and “be carefuls.” Betty took off her earrings, straightened some of her curls, and put on a longer dress. Visually, she appeared taller and less curvy. She began entering the workforce like her audience, taking on various jobs. Due to policy influences, the narrative also gradually returned to a more conservative style. Nevertheless, Betty Boop remained radiant, her popularity undiminished.

What’s more? Betty Boop’s connection to the Jazz Age was not limited her physical appearance alone. Jazz music, in fact, was integral to Betty’s world as well. As Richard Fleischer, son of Max Fleischer, noted in his book Out of the Inkwell: Max Fleischer and the Animation Revolution, the Betty Boop series “epitomized the Jazz Age” through its collaborations with famous jazz artists of the time and their music.

When synchronized sound technology was first introduced, Walt Disney Studios got in on the ground floor of using it in Steamboat Willie (1928). Fleischer Studios then followed and quickly incorporated the technology into the production of Betty Boop cartoons. This breakthrough allowed Fleischer Studios to bring Betty to life by inviting actress Mae Questel to voice her, providing the squeaky sweet tone which became one of her defining traits. The technology also helped to produce richer sound effects, vivid dialogue and integrated vocal singing, setting up the stage for the later highlights of jazz performances.

Riding the wave, legendary jazz singers and musicians like Baby Esther Jones and Helen Kane (who Betty was partially based on, though Kane later sued the studio for infringement of her right of publicity), Louis Armstrong, and Cab Calloway started appearing in the cartoon through multiple ways. In Betty Boop: Snow White (1933), Cab Calloway voiced Koko the Clown and sang his classic “St. James Infirmary Blues,” a mournful song about a deceased lover, in the scene where Koko follows Betty, who lies in an ice coffin carried by dwarfs [4:21-6:00].

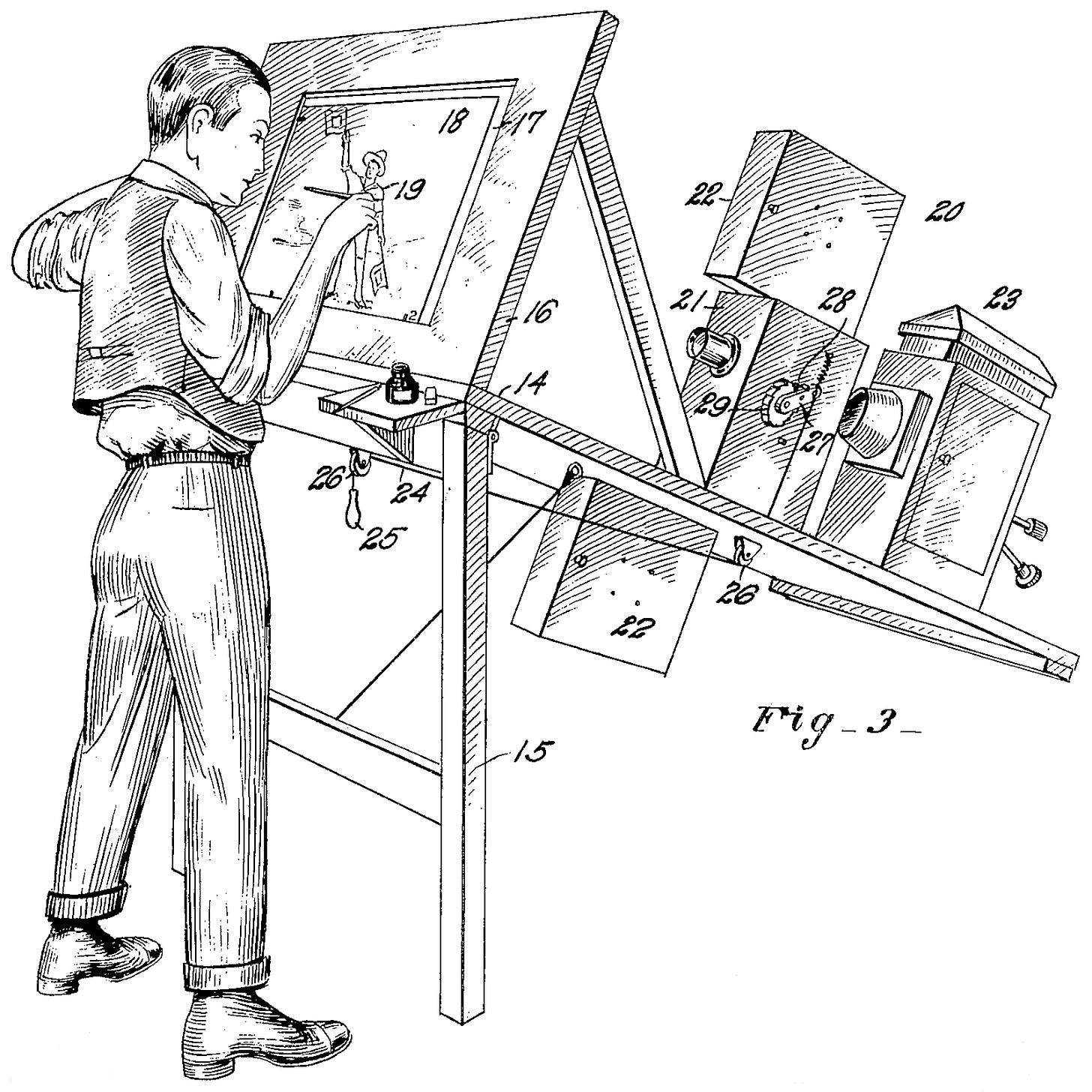

The Contribution of New Technologies & Techniques

Through rotoscoping, a groundbreaking technique invented by Max Fleischer that allowed animators to create realistic, fluid character movements by tracing over footage frame by frame, Koko’s movements synced with Calloway’s real-life dance moves. The cartoon recreated the artist’s performance on the animated characters with incredible precision, keeping its audience engaged with an immersive sensual experience. This blending of live jazz with animation brought an authenticity and vitality that made the Betty Boop series a genuine tribute to the Jazz Age, setting a new standard for animation.

Two Worlds, On Stage and Off

By the early 1930s, Betty Boop had become a worldwide icon. Her merchandise was everywhere: there were dolls, clothing, dinnerware, and countless other products. She even inspired the creation of personal comic strips and a weekly radio show, Betty Boop Fables. Audiences couldn’t get enough of her playful charm; the popularity was overwhelming.

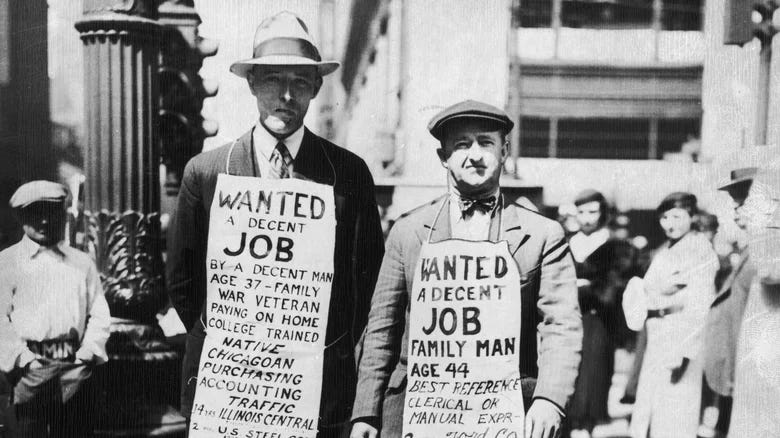

Of course, Betty’s rise was neither coincidence nor accident. The cultural and economic turmoil of the era, most notably the Great Depression, fueled her fame. The devastating economic crisis began with the Wall Street crash of 1929 and lasted for a decade. The Betty Boop series launched just as the Great Depression took hold and continued to release episodes throughout the chaotic period.

At first glance, it might seem uncanny that a lighthearted, whimsical cartoon would thrive while the entire American society was suffering from widespread poverty, unemployment, and despair. After all, the glittering world Betty Boop lived in looked nothing like the dark reality outside the theater doors.

Now, here is the truth: escapism was what made Betty Boop so successful. During the Great Depression, people were overwhelmed by stress and financial hardship. Already living a tough life, nobody was interested in stories that mirrored their pain. Instead, people sought happiness, relaxation, and most importantly, temporary distraction. And Betty Boop offered exactly what everybody needed.

With her dreamlike settings, flirtatious voice, playful energy and carefree personality, Betty provided the anxious viewers with an oasis of fantasy. Watching her cartoons allowed viewers to take a break from reality, temporarily escape their daily struggles, and indulge in the nostalgia of the Roaring Twenties—a world of glamour and music from the golden old days; a world where everything was still on track.

Betty Boop’s popularity resulted from her capability to meet this emotional need. She became not just entertainment but also comfort and hope, representing resilience and joy during one of America’s darkest times.

Now back to the Future…

It’s 2025, and Betty Boop is turning 100 in five years. Her cartoons remain iconic and magical even almost a century later. It’s simply incredible to think about this. As a masterpiece celebrated for its cultural impact, innovative techniques, and lasting historical significance, the Betty Boop series has always been one of people’s favorites. The cartoon proves that pop culture isn’t trivial in a modern world filled with noise and uncertainty. And may we, as viewers of animation, dreamers of reality, and survivors and fighters in life, always find our way to peace and joy.